Discovery made at Polytechnique Montréal in partnership with McGill University paves the way for new automated biological-sample analysis sytems

From conventional microfluidics to open-space microfluidics

Microfluidics refers to the manipulation of fluids in microscale devices. Commonly called “labs on a chip,” microfluidic systems are used to study and analyze very small-scale chemical or biological samples, replacing the extremely expensive and cumbersome instruments used for traditional biological analyses. Listed in 2001 among the “10 Emerging Technologies That Will Change the World” by the MIT Technology Review, microfluidics is considered just as revolutionary for biology and chemistry as microprocessors have been to electronics and IT, and it applies to a huge market.

Today, this young discipline, which began to take off in the 2000s with closed systems made up of microchannel networks, is itself being radically transformed by the discovery made by the group of researchers from Polytechnique and McGill University, which reinforces the theoretical and experimental foundations of open-space microfluidics.

This technology,whicheliminateschannels,competesfavourablywithconventionalmicrofluidics for certain types of analyses. Indeed, the classical configuration of closed-channel microfluidic devices provides several disadvantages: the scale of the channel cross-sections increases the stress that cells undergo when they are culture; and they are not compatible with the cell-culture standard, the Petri dish, which makes it hard for the industry to adopt it.

The new approach explored by Polytechnique and McGill University researchers is based on microfluidic multipoles (MFMs), a system of simultaneous fluid suction and aspiration through opposing micro-openings on a very small surface placed in a confined space that is less than 0.1 mm thick. “When they come into contact with one another, these jets of fluid form patterns that can be seen by dyeing them with chemical reagents,” says Professor Gervais. “We wanted to understand these patterns while developing a reliable method for modelling MFMs.”

Elegant visual symmetry reminiscent of the work of artist M. C. Escher

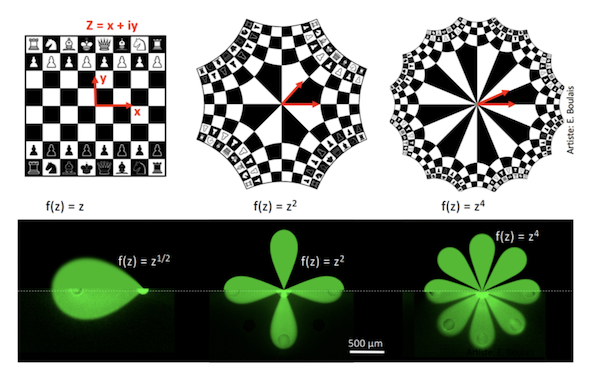

To understand these patterns, Professor Gervais’s team had to develop a new mathematical model for open multipolar flows. This model is based on a classical branch of mathematics known as conformal mapping that solves a problem related to a complex geometry by reducing it to a simpler geometry (and vice-versa).

PhD student Étienne Boulais first developed a model to study microjet collisions in a multifluidic dipole (an MFM with only two openings), and then, relying on this mathematical theory, extrapolated the model to MFMs with multiple openings. “We can make an analogy with a game of chess in which there is a version with four players, then six or eight, applying a spatial deformation while maintaining the same rules of the game,” he explains.

“When subjected to conformal mapping, the patterns created by fluid jet collisions form symmetrical images reminiscent of the paintings of Dutch artist M.C. Escher,” adds the young researcher, who has a passion for visual arts. “But far beyond its aesthetic appeal, our model allows us to describe the speed with which molecules move through fluids as well as their concentration. We have defined valid rules for all possible systems configurations of up to 12 poles in order to generate a wide variety of flow and diffusion patterns.”

The method is therefore a complete toolbox that will not only make it possible to model and explain the phenomena occurring in MFMs, but also explore new configurations. Thanks to this method, it is now possible to automate open-space microfluidic tests, which up until now have only ever been explored through trial and error.

Illustration of the mathematical transforms used, first on the image of a chessboard, then on microfluidic multipoles.

Fabrication of the device using 3D printing

The design and manufacture of the MFM device was accomplished by Pierre-Alexandre Goyette. This device is a small probe made out of resin using a low-cost 3D printing process and connected to a system of pumps and injectors.

“The expertise of Professor Juncker’s team in the detection of proteins by antibodies immobilized on a surface has been invaluable in managing the biological aspects of this project,” says the PhD student in biomedical engineering. “The results obtained with assays validated the accuracy of the models developed by my colleague Étienne.”

The device allows for the simultaneous use of several reagents to detect various molecules in the same sample, which saves biologists valuable time. For certain types of tests, the analysis time could be reduced from several days to a few hours, or even a matter of minutes. In addition, the versatility of this technology should make it usable for various analytical processes, including immunological and DNA tests.

Toward a microfluidic display?

Professor Gervais’s team is already considering a next step in his project: the development of a screen displaying a chemical image.

“It would be a sort of chemical equivalent of the liquid-crystal display,” Professor Gervais explains. “In the same way that we move electrons across a screen, we would send jets of fluid at various concentrations that would react with a surface. Together, they would form an image. We are very excited to move forward with this project, for which we have obtained a provisional patent.”

Reinvention of diagnostic procedures and medical-treatment follow-up

For now, the technology developed by this research team is aimed at the fundamental research market. “Our processes make it possible to expose cells to many reagents simultaneously,” Professor Gervais says. “They can help biologists study the interactions between proteins and reagents on a large scale, increasing the amount and quality of information obtained during assays.”

He explains that subsequently, the pharmaceutical market will also be able to benefit from new methods of screening-system automation resulting from the discovery. Lastly, it opens up a new avenue for drug discovery by facilitating patient cell culture and exposure to various drug agents to determine which ones they respond to best.

About Polytechnique Montréal

Founded in 1873, Polytechnique Montréal, technological university, is one of Canada’s largest engineering teaching and research institutions. It is the Québec leader for the scope of its engineering research activities. It is located on the campus of Université de Montréal, the largest French-language university campus in the Americas. With over 49,000 graduates, Polytechnique Montréal has educated 22% of the current members of the Ordre des ingénieurs du Québec. The institution offers more than 120 programs. Polytechnique has 260 professors and 8,600 students. It has a global annual budget of $215 million, including a research budget of $81 million.

Article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-09740-7

Media kit: http://bit.ly/2GsUxOH

Media contact:

Florence Scanvic

Communications Advisor

Polytechnique Montréal

514340-4711, extension2730

Florence.Scanvic [at] polymtl.ca